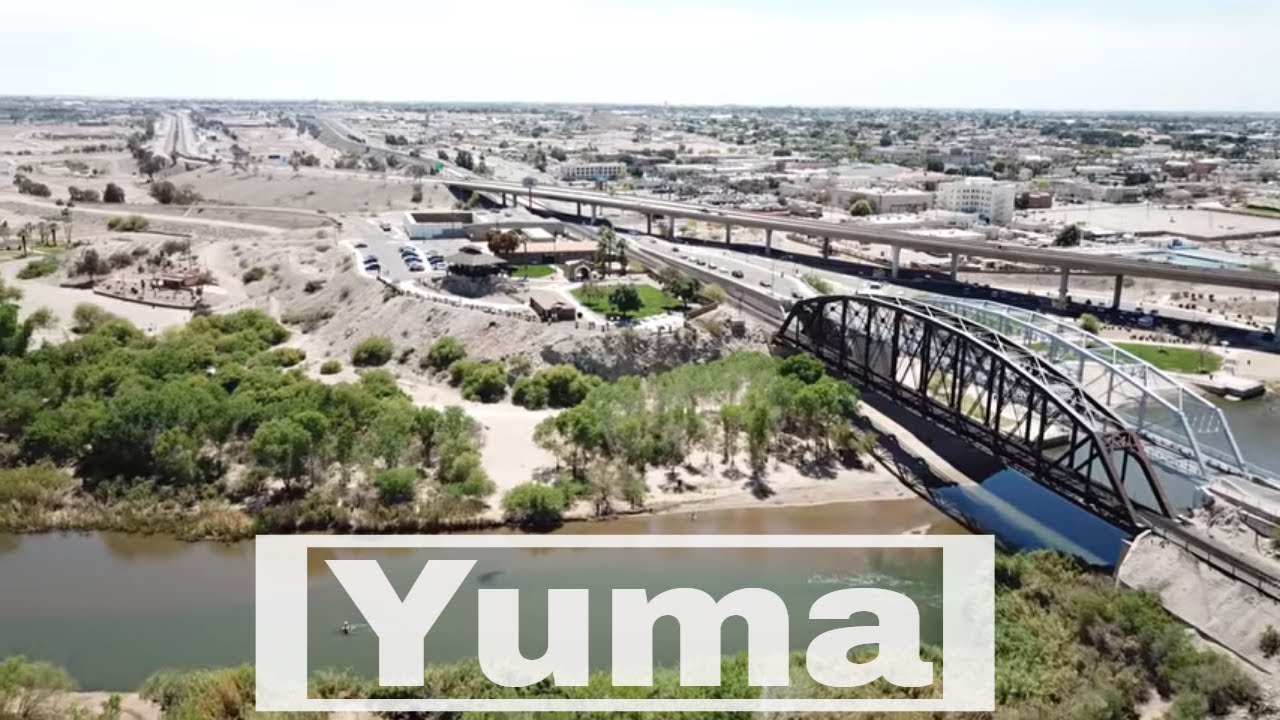

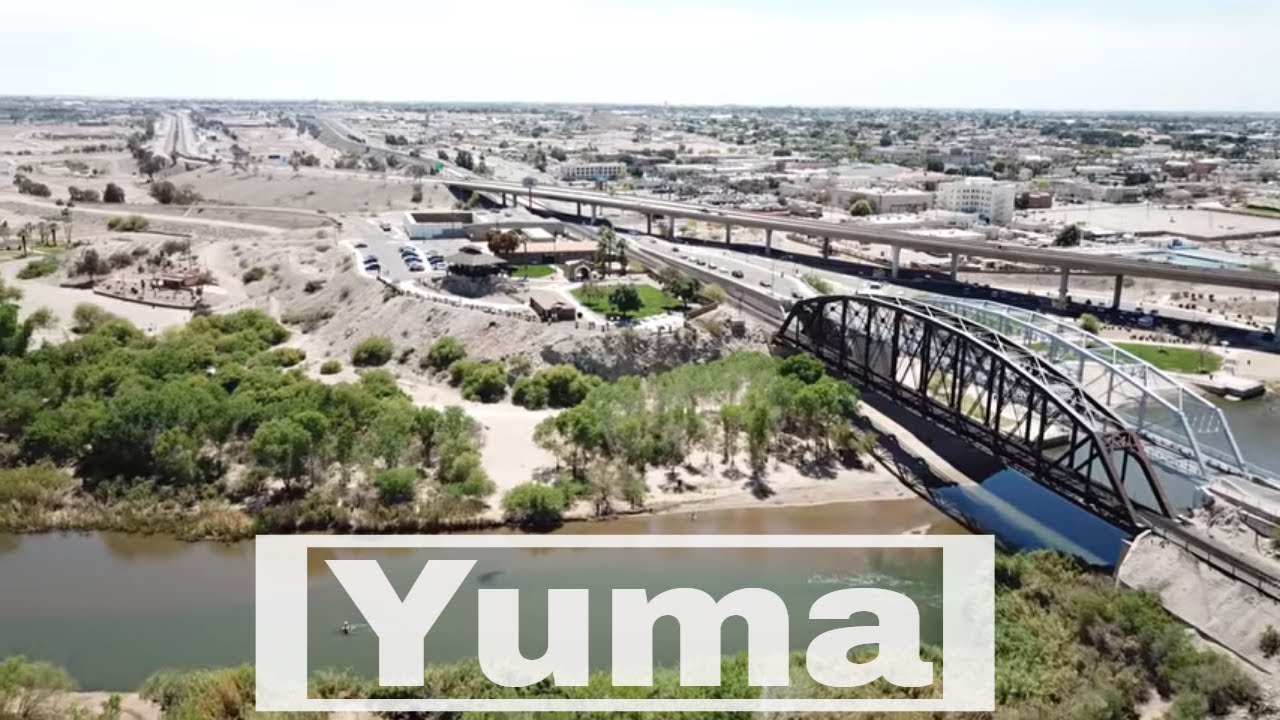

- : Yuma, Arizona

- : Arizona

- : #

Standing on the banks of the Colorado River in Yuma today, it is hard to imagine the river in its original, untamed state. Yet, in the days before dams were constructed up and down its length, the waters of the Colorado shaped the

geography – and history – of the entire Southwest.

In those days, the full volume of water that now sustains life in seven western states and two countries ran by Yuma’s doorstep – and often ran wild. The course of the river was unpredictable from year to year and from season to season, and in the table-flat floodplains where it met the Gila, the riverbed often stretched across 15 miles of silty bottoms laced with unexpected back channels and even pockets of quicksand. Getting across was no easy matter, even when the river was not in flood.

But at the place that would become Yuma, two outcroppings of granite held their place against the river’s might and squeezed it into a narrower channel. Here the waters ran swift, but the banks held firm and the passage was, if still hazardous, at least predictable. So from the time the earliest people came to the area, this was known as the easiest and safest place to cross the river: the Yuma Crossing.

Early Explorers

The first Europeans arrived in the Yuma area in 1540 – some 80 years before the Pilgrims set foot on Plymouth Rock – when Spanish expeditions led by the Hernando de Alarcon and Melchior Diaz sailed up the Colorado from the Sea of Cortez. They noted the natural crossing of the Colorado as a potential site for settlement because of its strategic location.

But these Spanish explorers also found thriving communities already in existence along the banks of the river – ancestors of the present-day Quechan and Cocopah tribes – hunting, fishing and growing crops. The explorers called the Indians the Yumas, from the Spanish word for smoke (humo), because smoke from their cooking fires filled the valley as the Spaniards surveyed the Crossing from “Indian Hill.”

Early expeditions aside, the Indians of the Yuma area were left largely undisturbed until the 1680s, when Father Eusebio Kino arrived in Sonora to establish missions and convert the native people to Christianity. Father Kino’s expeditions throughout what is now Arizona, New Mexico and California mapped an area 200 miles wide and 250 miles long, including what is now Yuma County. He led the first land expedition to Baja California, confirming that it is a peninsula, not an island.

It was not until 1774 that Yuma became firmly fixed on maps of New Spain. That is when the viceroy of New Spain charged the captain of the presidio at Tubac (near present-day Tucson) with finding a practical overland route from Sonora to northern California. Juan Bautista de Anza arrived in Yuma in January and established relations with the Quechans, who controlled the river crossing.

That friendly contact proved critical to the survival of Anza’s men when the expedition became lost in the wilderness of sand dunes to the west and was forced to retrace its steps to the banks of the Colorado. It was not until the end of March that Anza and some of his men finally arrived at Mission San Gabriel (near present-day Los Angeles). But it was the Anza Trail – through the Yuma Crossing – that opened the way for Spanish settlement of Alta (upper) California. In terms of the larger world, Yuma was “on the map.”

However, this increased the pressure for the Spanish to control the strategic Yuma Crossing and to convert the Quechan. In 1781, the Quechans rebelled against Spanish oppression, injustice and a significant loss of their crops and food stores. The Spanish settlement at the Crossing was destroyed with many Spaniards killed and taken captive. The Spanish largely retreated and never again tried to dominate the Quechan or control the Yuma Crossing.

By the time Mexico won its independence from Spain in 1821, a decade of war had destroyed the silver-mining industry and left the country bankrupt. The northern presidios and missions began to wither as mountain men and other explorers from the United States moved into the area.